With the help of the larger U.S.-Canada community, a team of scientists has sought to understand how an alpine mammal sheds its winter coat.

Cover Image: A camera trap on loan to Dr. Kate Nowak from WCS Canada captures a billy mountain goat at Pooly Canyon, Yukon, Canada

What do goat hair, climate change, and community science have in common? It turns out, quite a lot. Humans can take off their winter coats when the weather gets warmer — but animals can’t. And what if it starts getting warmer earlier each year? If you’re a mountain goat, can you start shedding your coat earlier, or do you have to change your behavior to adapt to warmer temperatures (and if so, how)?

From Tanzanian Monkeys and Elephants to Mountain Goats

I talked to wildlife conservation scientist Dr. Kate Nowak about the Mountain Goat Molt Project.

From a young age, Kate was interested in wild mammals, their adaptability, and their interactions with people. Her work has taken her around the world to places like Costa Rica, South Africa and Tanzania. Her passion for conservation has led her to contribute to National Geographic, the Southern Tanzania Elephant Program, and The Safina Center among others. After years of itinerant conservation work, in 2016 Kate returned to North America.

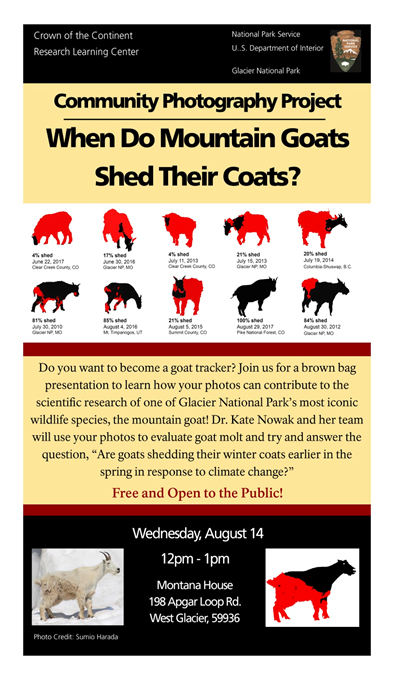

While she was a visiting scientist at Colorado State University, she attended a conference in Estes Park, home of Rocky Mountain National Park where she met ecologist Greg Newman, Director of CitSci.org. CitSci is a growing citizen science platform operated by a team in the Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory. At the time, Kate was thinking about how mountain goats are dealing with climate warming and thermal stress because they’re so well-adapted to cold environments (like the mountain alpine). Could how and when they shed their thick coats be surmised from photographs taken by people across mountain goat range? Learning about CitSci.org was an “Ah-ha” moment for Kate.

In partnership with CitSci.org and later Zooniverse, and using “community photography”, Kate and her team started to study whether mountain goats were showing changes in coat molting in recent years. “With the help of “people-powered research”, the scientists could garner many more photos than they could have ever captured on their own.

Crowdsourcing Photos to Study Patterns

Kate explains how using the CitSci.org platform and starting to leverage tools available in Zooniverse has helped this research. The problem is sourcing enough photographs and processing these to estimate shed extents, which means that by having access to a wide community of naturalists plus assistance with processing, the mountain goat dataset can grow.

The project received photo submissions from members of the public from Colorado, the southern extent of mountain goat range, north to Alaska and the Yukon. In the Yukon, the team filled a photo gap by camera-trapping wild and captive mountain goats. While most of the photographs they amassed were recent, there was one from as far back as 1948. It would be difficult, if not impossible, for a scientific research team to collect the same amount of data that citizen scientists can collect and share.

Analyzing Photos Takes A Crowd Too, and You Can Help!

So what do researchers do with hundreds of photos of mountain goats? Once photos started streaming in from citizen scientists, the focus shifted to analysis. Kate and her research team put each photo into Photoshop and estimated the shed versus unshed area (i.e., number of pixels) of each animal’s coat. The ratio of shed to unshed pixels on each photo, combined with the date and location, and the sex and kid status of the mountain goat, were all logged to start to provide insight into the timing of molt and what affects it.

To help the team, Kate’s sister created this tutorial for citizen scientists, researchers, and photographers to learn how to use Adobe Photoshop software to analyze photos like this. But the research did not stop there.

Artificial Intelligence meets Mountain Goats (and Moose!)

Kate has ideas in the works for future image analysis. With the help of high school senior Aditya Mehta, and a Microsoft AI for Earth computing grant, the team is developing a program to automate estimates of coat molt from photos. Amy Panikowski, a scientist and member of the research team, is testing the same method on photos of moose, which lose their hair as a result of winter ticks, in a University of Toronto study led by PhD student Emily Chenery. The team is confident that techniques they’re using with mountain goats can be used with photos of other species such as moose as well.

Are mountain goats changing their molting patterns due to climate change?

It’s still too soon to determine whether climate is affecting the timing of goat coat molting. The researchers have detected relationships between elevation and latitude and coat molt timing — molt is delayed higher up suggesting temperature plays a role. Findings from the project on sex effects on molt are consistent with long-term research, which provides confidence in the quality of the crowdsourced data. Specifically, males shed first, followed by females then lastly females with kids.

This project has inspired Kate and colleagues to encourage and leverage community science in the future to better understand phenology of life history events such as molting as well as capture the range of mammals’ behavioral adaptations to a changing climate. In the meantime, Kate has shared the team’s methods and preliminary findings at meetings of the American Society of Mammalogists and the Yukon Biodiversity Forum. They also have a paper in review. Interest in projects that rely on community science is growing and, Kate hopes, paves an interactive way to boost the public’s scientific interest and literacy as well as scientists’ responsibility to communicate findings and address questions of societal interest.

Inspiring People to Study Change with Citizen Science

Kate hopes the Mountain Goat Molt Project will serve as an example for others to consider using crowdsourced photos to study how animals cope with change. Studying change, especially in physiological processes and in animal behavior too, is not easy. But Kate hopes their attempts will inspire others to take on the challenge.

How can you get involved in the Mountain Goat Molt Project?

You can contribute your mountain goat photos to the Mountain Goat Molt Project on CitSci.org and browse the wide range of other projects by signing up for an account and adding data! You can also participate by helping analyze data including mountain goat photos in Zooniverse.

Keep Exploring

Mountain Goats aren’t the only animals sensitive to climate change stress. Check out our stories about other critters and ecosystems citizen scientists are watching carefully:

The Front Range Pika Project: Why Pikas? (Part 1)

The Front Range Pika Project: Emerging Science (Part 2)

BioBlitz Inspires Inclusion of Citizen Science in Pollinator Research

Support Provided By

The mountain goat molt research was supported with funding from the U.S. National Park Service and Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative. Additional support was provided by the Wildlife Conservation Society and Wildlife Conservation Society Canada. Kate was also supported with fellowships from The Safina Center, and an equipment loan from Kokopelli Packraft.

3 comments on “How to Get a Better Picture of Mountain Goats with Community Science”