Earlier this fall, I had the chance to lead a Lunch N’ Learn at Colorado State University on a deceptively simple but endlessly complex subject: the science of science communication.

Why “the science of science communication”? The phrase may sound recursive, but it reflects an important truth: communication itself can be a subject of research. In fact, it’s what I focused on during my PhD! Just as we study climate change or ecosystems, we also study how information moves between scientists, decision-makers, and the public. And with better communication, we can do better science.

I anchored the session with this definition from the National Environmental Education Foundation: “Science communication involves distilling the technical aspects of scientific research into language that the public can better relate to and understand.”

In other words, science communication is communicating science to the public — and by “public,” we mean everyone.

You can watch a recording of my talk, below, but I summarized the high-level takeaways in this blog post.

My path into this work

I shared some of my own background to show how many different doors can open into science communication:

- PhD in Climate Change Communication, University of Florida (UF/IFAS Extension). My dissertation tested “Digital Field Experiences,” localized webinars about climate hazards with concrete calls to action.

- Citizen science leadership:

- CitSci – where I now serve as Communications Lead. It’s a platform that lets anyone start, manage, or join citizen science projects. I’m particularly proud of my “Quick Guide to Starting a Citizen Science Project” and “Citizen Science for Educators” blog posts.

- SciStarter – a global database of participatory science projects, where I’ve directed major campaigns like Citizen Science Month (480% increase in contributions during April 2020).

- Human Computation Institute – which, among other projects, runs Stall Catchers, a gamified biomedical research platform where volunteers analyze blood vessel images to advance Alzheimer’s research.

- UF Department of Psychiatry – where I helped package the research and writings of Dr. Richard C. Christensen into a textbook and curriculum, weaving in patient artwork by homeless and underserved patients to humanize the science.

- Social enterprise & systems change: through Rally (the City of Orlando’s Social Enterprise Accelerator) and the Central Florida Foundation.

- Florida Community Innovation (FCI) – a nonprofit I co-founded, where I volunteer so all the money can go to student workers. We build civic tech with communities, including the Florida Resource Map that connects social workers to food, shelter, and other resources.

Each role taught me the same lesson: there’s no single right way to communicate science, but there are frameworks we can learn from.

Defining the terms

We started the session by grounding in some shared definitions. Here’s how I generally define the following terms:

- Research: a systematic way of investigating the world to create new knowledge. This spans natural sciences, history, social sciences, and more.

- Citizen science / participatory science: any way the public (that’s anyone!) contributes to scientific discovery — from collecting data to analyzing it. Data can be numbers (quantitative) or words and pictures (qualitative).

- Science communication: the act of sharing science with people beyond your immediate research peers, ideally through two-way dialogue.

Why communicate science?

Our discussion surfaced many reasons:

- Curiosity and wonder: People want to feel part of something bigger than themselves. Citizen science is one avenue.

- Better decision-making: From COVID-19 to climate hazards, timely communication can shape public health, resilience, and policy.

- Democracy: Science is part of our civic DNA. The Founders were scientists (think Franklin, Jefferson), and communicating science strengthens democratic participation.

- Funding and support: Sharing your research can help attract grants, crowdfunding, or volunteers.

- Community and relationships: Sometimes communication isn’t about immediate outcomes; it’s about building trust over time.

I personally communicate about science because I want to empower a better world, and knowledge is power when we feel hopeless and scared: it gives us a foundation to make good decisions. As Wes Nisker once said: “If you don’t like the news, go out and make some of your own.”

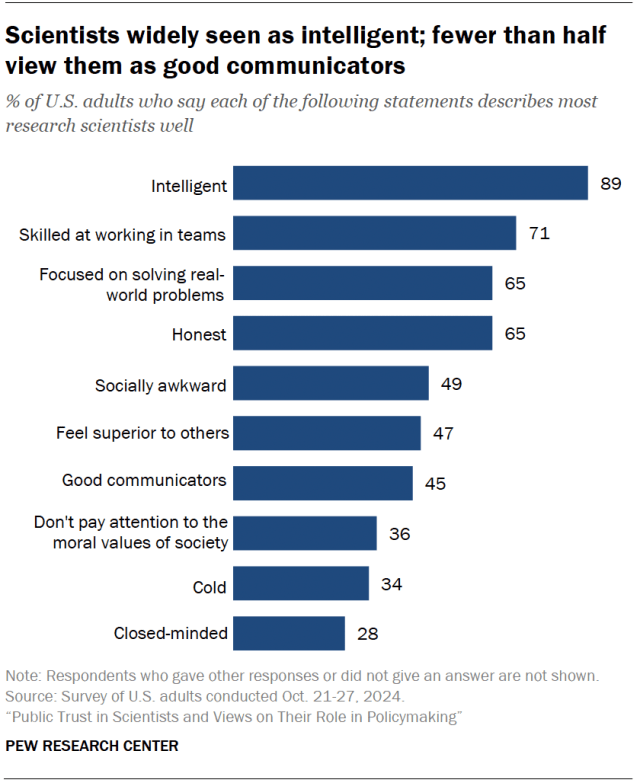

The public perception challenge

One challenge is that while the public broadly sees scientists as intelligent, fewer than half view them as good communicators.

Headlines echo declining trust. Check out some I pulled, below:

That gap makes dialogue harder, but also underscores why communication matters: we need to build trust so we can do science the public supports.

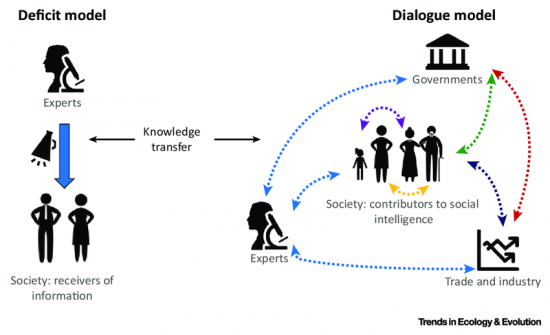

Two models of communication

- Deficit model: The scientist speaks, the public listens. Sometimes necessary, but limited.

- Dialogue model: Two-way exchange, where the public’s needs, language, and insights shape research.

We focused on the dialogue model. It surfaces not only what benefits the public, but also how scientists are better off with two-way communication: they get new ideas, potential volunteers, funding, and maybe even some new friends.

A six-step framework

Here’s the process I shared, supported by examples from my own work

- Know Thyself – Define your role. Example: My UF Psychiatry project, where I wasn’t the physician, but could elevate Dr. Christensen’s work serving homeless individuals through evidence-based approaches, all via my work empowering the curriculum and patient art.

- Know Your Audience – Identify stakeholders. Example: SciStarter’s Citizen Science Month pivoted during April 2020 by listening to facilitators and the general public about their needs for virtual programming, leading to a 480% participation spike.

- Know Your Message – Clarify your “why.” Example: With FCI’s Resource Map, we learned to use the language social workers preferred (“resources” vs. “apps”), building trust with partners like Sharon and Henrietta, two community members who had spent their careers working in an underserved part of Orlando.

- Devise a Plan – Choose your venues and allies. Example: EMERGE, a NASA-funded Florida project engaging the public in mosquito habitat mapping, spread via UF/IFAS Extension listservs, SciStarter’s thousands of Florida users, and Dream in Green’s teacher networks.

- Take Action – Implement. Example: My Digital Field Experiences webinars localized climate hazards across Florida counties, pairing calls to action with honesty about scope.

- Reflect – Learn and adapt. Example: The Leave No Trash University Challenge on CitSci engaged universities in the United States and Nigeria, teaching us to adjust protocols (and even add competitive elements) based on feedback.

Lessons from the room

Participants added their own insights:

- Asmita, a graduate researcher, emphasized that even brilliant scientists must share their work clearly with the public.

- Greg shared how reframing research for ranchers (livestock weight gain vs. biomass predictors) built buy-in, and how titles like “Gulls Eating Stuff” beat jargon every time.

- Anika described her lab’s project with municipal water managers, illustrating how stakeholder listening sessions can guide tool design.

These discussions reinforced that good communication is situational: what resonates in a CSU lab might flop at a Fort Collins community meeting, and vice versa.

Practical tools

To move from theory to practice, I shared the Science Communication Brainstorm worksheet.

It asks you to reflect on:

- What science are you working on?

- Who are your stakeholders?

- What’s your message?

- How will you communicate, and who can help?

- What’s your step-by-step plan?

- What’s next?

Download the worksheet and fill it out yourself! 🙂

Key takeaways

If you remember nothing else:

- Know your goals. Are you seeking volunteers, recognition, funding, or dialogue?

- Know your audience. Tailor language and venue — whether that’s SciStarter’s newsletter, CitSci’s platform, a podcast, or a town hall.

- End with a call to action. When you have attention, give people something tangible to do.

So here’s my call to action: Create a free CitSci account to start, join, or explore projects.

And if you’d like to keep the conversation going, email me at caroline.nickerson@colostate.edu. I’d love to brainstorm your science communication journey.